Is your team building or scaling AI agents?(Sponsored)One of AI’s biggest challenges today is memory—how agents retain, recall, and remember over time. Without it, even the best models struggle with context loss, inconsistency, and limited scalability. This new O’Reilly + Redis report breaks down why memory is the foundation of scalable AI systems and how real-time architectures make it possible. Inside the report:

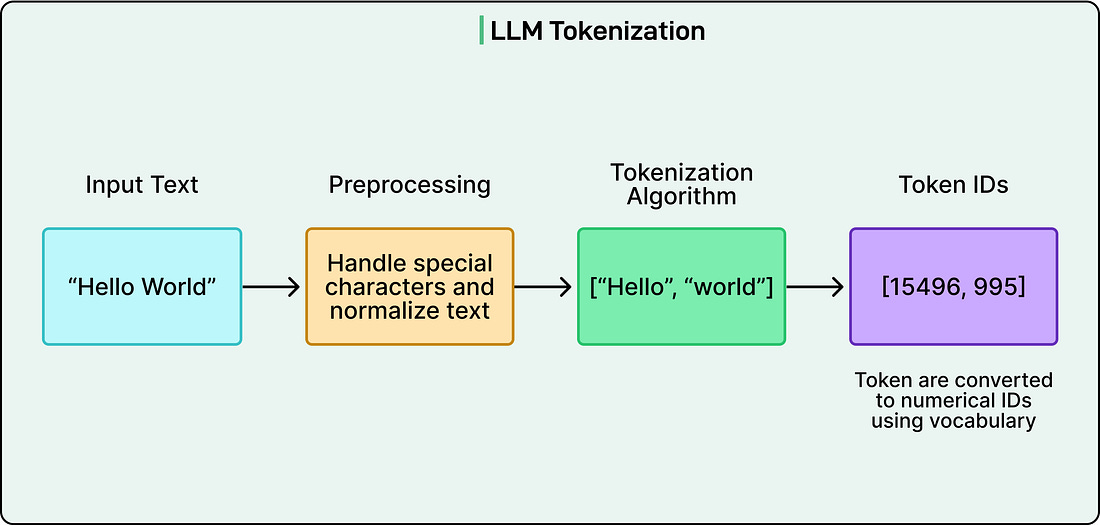

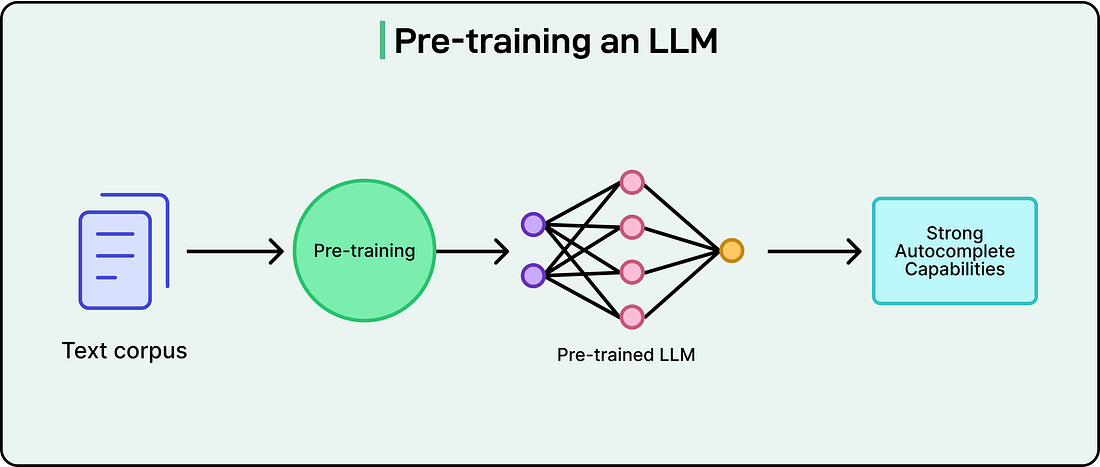

The first time most people interact with a modern AI assistant like ChatGPT or Claude, there’s often a moment of genuine surprise. The system doesn’t just spit out canned responses or perform simple keyword matching. It writes essays, debugs code, explains complex concepts, and engages in conversations that feel remarkably natural. The immediate question becomes: how does this actually work? What’s happening under the hood that enables a computer program to understand and generate human-like text? The answer lies in a training process that transforms vast quantities of internet text into something called a Large Language Model, or LLM. Despite the almost magical appearance of their capabilities, these models don’t think, reason, or understand like human beings. Instead, they’re extraordinarily sophisticated pattern recognition systems that have learned the statistical structure of human language by processing billions of examples. In this article, we will walk through the complete journey of how LLMs are trained, from the initial collection of raw data to the final conversational assistant. We’ll explore how these models learn, what their architecture looks like, the mathematical processes that drive their training, and the challenges involved in ensuring they learn appropriately rather than simply memorizing their training data. What Models Actually Learn?LLMs don’t work like search engines or databases, looking up stored facts when asked questions. Everything an LLM knows is encoded in its parameters, which are billions of numerical values that determine how the model processes and generates text. These parameters are essentially adjustable weights that get tuned during training. When someone asks an LLM about a historical event or a programming concept, the model isn’t retrieving a stored fact. Instead, it’s generating a response based on patterns it learned by processing enormous amounts of text during training. Think about how humans learn a new language by reading extensively. After reading thousands of books and articles, we develop an intuitive sense of how the language works. We learn that certain words tend to appear together, that sentences follow particular structures, and that context helps determine meaning. We don’t memorize every sentence we’ve ever read, but we internalize the patterns. LLMs do something conceptually similar, except they do it through mathematical processes rather than conscious learning, and at a scale that far exceeds human reading capacity. In other words, the core learning task for an LLM is simple: predict the next token. A token is roughly equivalent to a word or a piece of a word. Common words like “the” or “computer” might be single tokens, while less common words might be split into multiple tokens. For instance, “unhappiness” might become “un” and “happiness” as separate tokens. During training, the model sees billions of text sequences and learns to predict what token comes next at each position. If it sees “The capital of France is”, it learns to predict “Paris” as a likely continuation. What makes this remarkable is that by learning to predict the next token, the model inadvertently learns far more. It learns grammar because grammatically correct text is more common in training data. It learns facts because factual statements appear frequently. It even learns some reasoning patterns because logical sequences are prevalent in the text it processes. However, this learning mechanism also explains why LLMs sometimes “hallucinate” or confidently state incorrect information. The model generates plausible-sounding text based on learned patterns that may not have been verified against a trusted database. Gathering and Preparing the KnowledgeTraining an LLM begins long before any actual learning takes place. The first major undertaking is collecting training data, and the scale involved is staggering. Organizations building these models gather hundreds of terabytes of text from diverse sources across the internet: websites, digitized books, academic papers, code repositories, forums, social media, and more. Web crawlers systematically browse and download content, similar to how search engines index the web. Some organizations also license datasets from specific sources to ensure quality and legal rights. The goal is to assemble a dataset that represents the breadth of human knowledge and language use across different domains, styles, and perspectives. However, the raw internet is messy. It contains duplicate content, broken HTML fragments, garbled encoding, spam, malicious content, and vast amounts of low-quality material. This is why extensive data cleaning and preprocessing become essential before training can begin. The first major cleaning step is deduplication. When the same text appears repeatedly in the training data, the model is far more likely to memorize it verbatim rather than learn general patterns from it. If a particular news article was copied across a hundred different websites, the model doesn’t need to see it a hundred times. Quality filtering comes next. Not all text on the internet is equally valuable for training. Automated systems evaluate each piece of text using various criteria: grammatical correctness, coherence, information density, and whether it matches patterns of high-quality content. Content filtering for safety and legal compliance is another sensitive challenge. Automated systems scan for personally identifiable information like email addresses, phone numbers, and social security numbers, which are then removed or anonymized to protect privacy. Filters identify and try to reduce the prevalence of toxic content, hate speech, and explicit material, though perfect filtering proves impossible at this scale. There’s also filtering for copyrighted content or material from sources that have requested exclusion, though this remains both technically complex and legally evolving. The final preprocessing step is tokenization, which transforms human-readable text into a format the model can process. See the diagram below: Rather than working with whole words, which would require handling hundreds of thousands of different vocabulary items, tokenization breaks text into smaller units called tokens based on common patterns. A frequent word like “cat” might be a single token, while a rarer word like “unhappiness” might split into “un” and “happiness.” These tokens are then represented as numbers, so “Hello world” might become something like [5431, 892]. This approach, often using methods like Byte Pair Encoding, allows the model to work with a fixed vocabulary of perhaps 50,000 to 100,000 tokens that can represent essentially any text. All of this preprocessing work establishes a fundamental principle: the quality and diversity of training data directly shape what the model will be capable of. A model trained predominantly on scientific papers will excel at technical language but struggle with casual conversation. A model trained on diverse, high-quality data from many domains will develop broader capabilities. The Learning ProcessBefore training begins, an LLM starts in a state of complete ignorance. Its billions of parameters are set to small random values, carefully chosen from specific statistical distributions but essentially meaningless. If we fed text to this untrained model and asked it to predict the next token, it would produce complete gibberish. The entire purpose of training is to adjust these random parameters into a configuration that encodes useful patterns about language and knowledge. The training process follows a continuous loop that repeats billions of times.

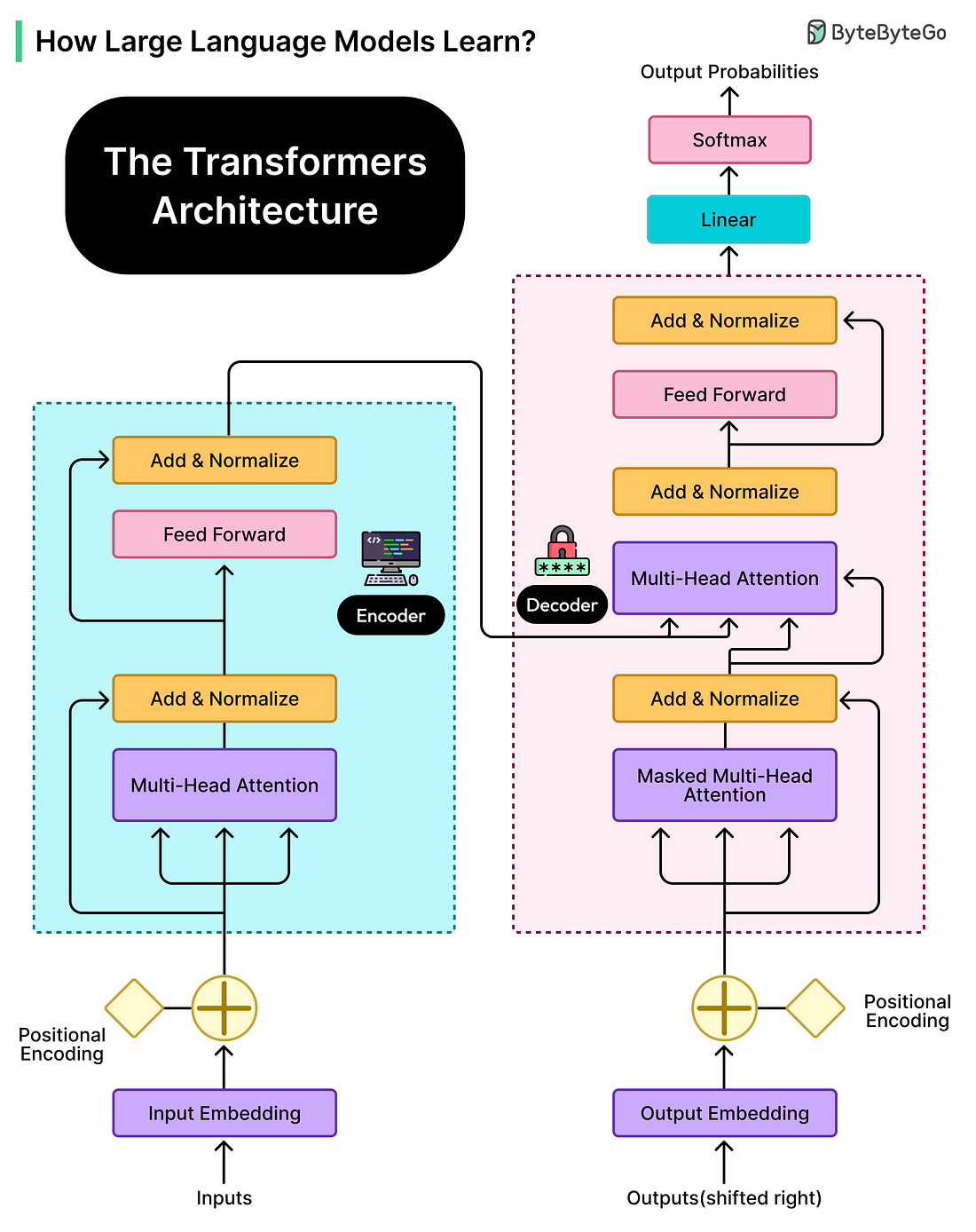

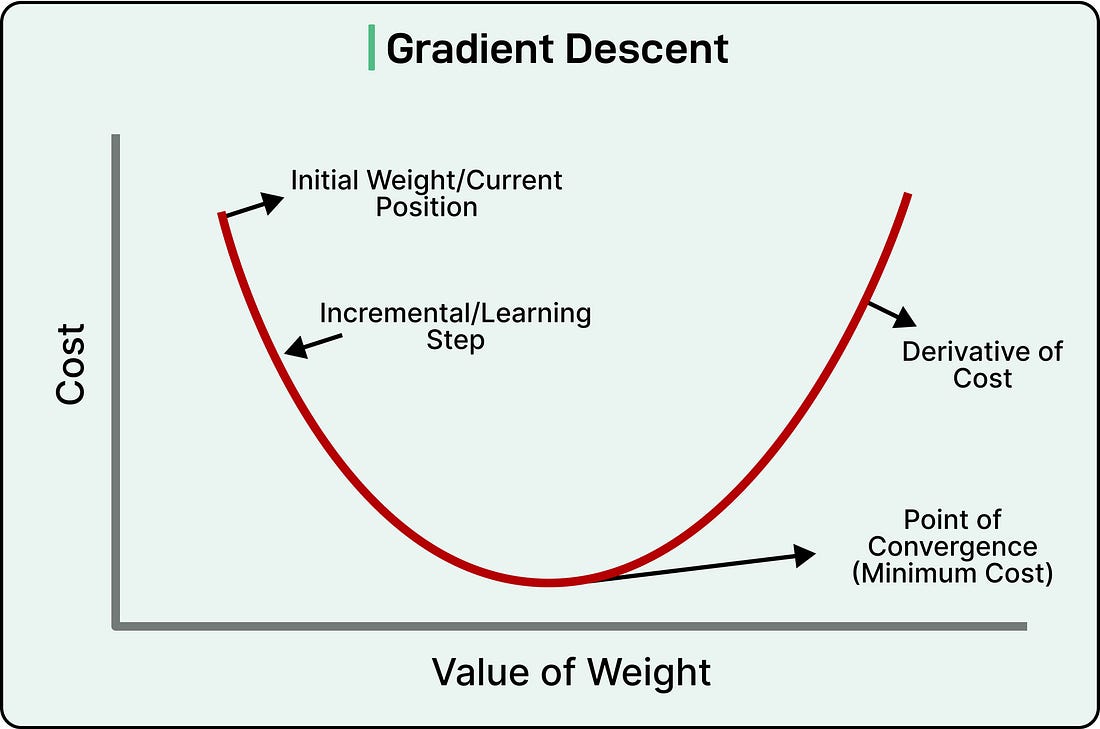

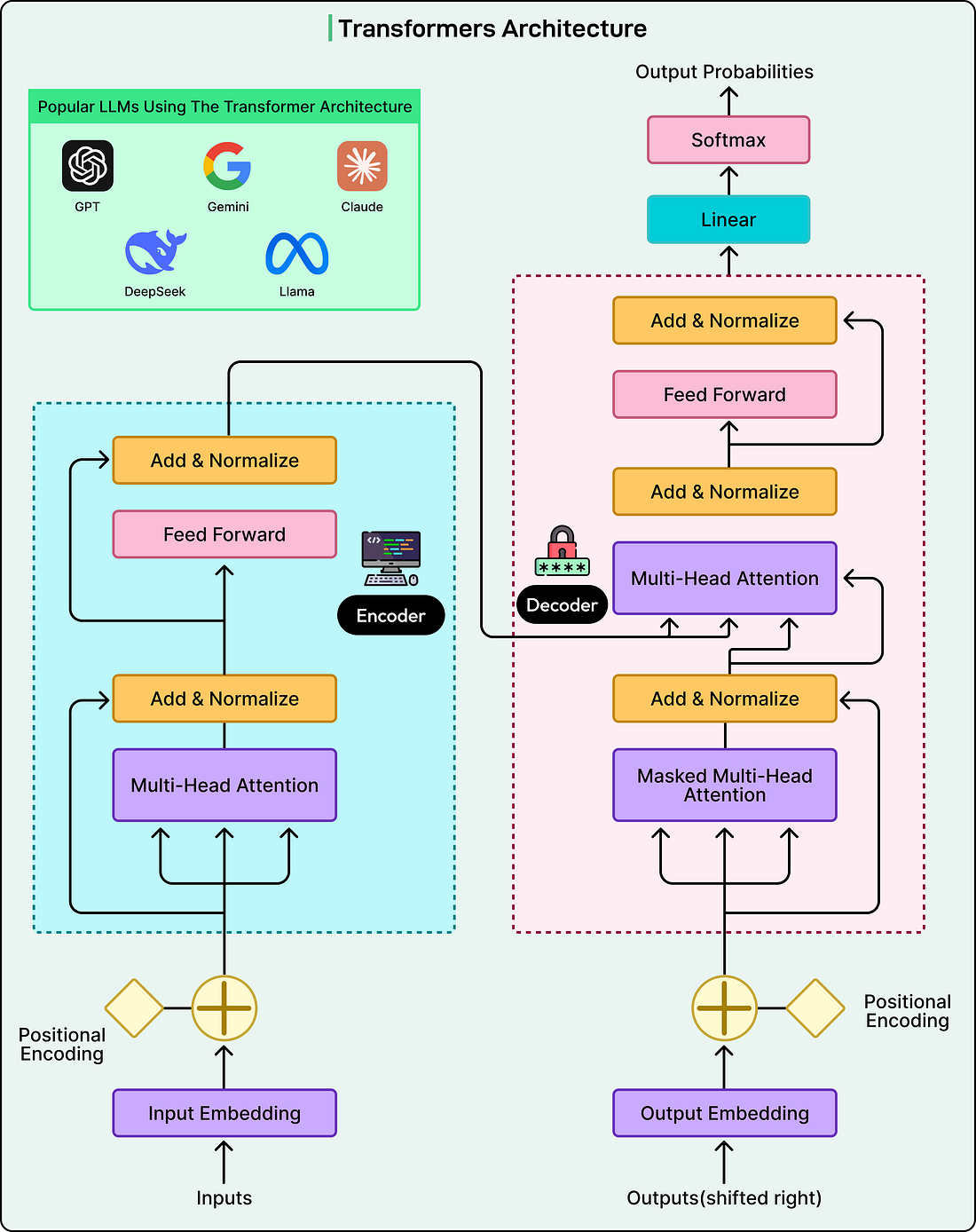

The challenge now is figuring out how to adjust billions of parameters to reduce this loss. This is where gradient descent comes in. Imagine standing in a foggy, hilly landscape where the goal is to reach the lowest valley, but visibility is limited to just a few feet. The strategy would be to feel which direction slopes downward at the current position, take a step in that direction, reassess, and repeat. Gradient descent works similarly in an abstract mathematical space. The “landscape” represents how wrong the model’s predictions are across all possible parameter configurations, and the algorithm determines which direction in this space leads downward toward better predictions. Through a process called backpropagation, the training system efficiently calculates exactly how each of the model’s billions of parameters contributed to the error. Should parameter number 47,293,816 be increased slightly or decreased slightly to reduce the loss? Backpropagation works backward through the model’s layers, calculating gradients that indicate the direction and magnitude each parameter should change. All parameters are then adjusted simultaneously by tiny amounts, perhaps changing a value by 0.00001. No single adjustment is meaningful on its own, but across trillions of these microscopic changes, the model gradually improves. This process repeats continuously over weeks or even months of training on massive clusters of specialized processors. Modern LLM training might use thousands of GPUs or TPUs working in parallel, consuming megawatts of electricity and costing tens of millions of dollars in computational resources. The training data is processed multiple times, with the model making billions of predictions, calculating billions of loss values, and performing trillions of parameter adjustments. What emerges from this process is genuinely remarkable. No individual parameter adjustment teaches the model anything specific. There’s no moment where we explicitly program in grammar rules or facts about the world. Instead, sophisticated capabilities emerge from the collective effect of countless tiny optimizations. The model learns low-level patterns like how adjectives typically precede nouns, mid-level patterns like how questions relate to answers, and high-level patterns like how scientific discussions differ from casual conversation. All of this arises naturally from the single objective of predicting the next token accurately. By the end of pretraining, the model has become extraordinarily good at its task. It can predict what comes next in text sequences with accuracy, demonstrating knowledge across countless domains and the ability to generate coherent, contextually appropriate text. However, it’s still fundamentally an autocomplete system. If given a prompt that starts with a question, it might continue with more questions rather than providing an answer. The model understands patterns but hasn’t yet learned to be helpful, harmless, and honest in the way users expect from a conversational assistant. That transformation requires additional training steps we’ll explore in later sections. The Architecture: Transformation and AttentionThe training process explains how LLMs learn, but the model’s structure determines what it’s capable of learning. The architecture underlying modern LLMs is called the Transformer, introduced in a 2017 research paper with the fitting title “Attention Is All You Need.” This architectural breakthrough made today’s sophisticated language models possible. Before Transformers, earlier neural networks processed text sequentially, reading one word at a time, much like a human reads a sentence from left to right. This sequential processing was slow and created difficulties when the model needed to connect information that appeared far apart in the text. If important context appeared at the beginning of a long paragraph, the model might struggle to remember it when processing the end. Transformers revolutionized this by processing entire sequences of text simultaneously and using a mechanism called attention to let the model focus on relevant parts of the input regardless of where they appear. The attention mechanism is best understood through an example. Consider the sentence: “The animal didn’t cross the street because it was too tired.” When a human reads this, we instantly understand that “it” refers to “the animal” rather than “the street.” We do this by paying attention to context and meaning. The attention mechanism in Transformers does something mathematically analogous. For each word the model processes, it calculates attention scores that determine how much that word should consider every other word in the sequence. These attention scores are learned during training. For example, the model learns that pronouns should pay high attention to their antecedents, that words at the end of sentences should consider the beginning for context, and countless other patterns that help interpret language correctly. Transformer models are organized in layers, typically dozens of them stacked on top of each other. Each layer contains attention mechanisms along with other components, and information flows through these layers sequentially. The interesting aspect is that different layers learn to extract different kinds of patterns.

The information flowing through these layers takes the form of vectors, which are essentially lists of numbers that encode the meaning and context of each token position. At each layer, these vectors get transformed based on the model’s parameters. Think of it as the model continuously refining its understanding of the text. The raw tokens enter at the bottom, and by the time information reaches the top layers, the model has developed a rich, multi-faceted representation that captures syntax, semantics, context, and relationships within the text. This architecture provides several crucial advantages, which are as follows:

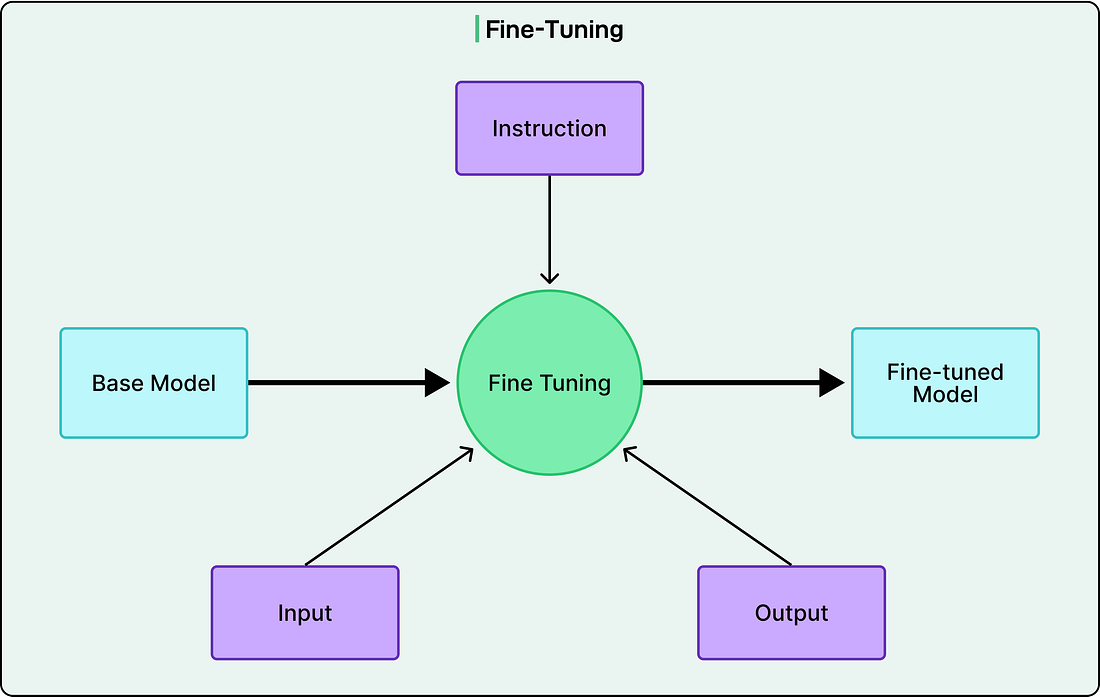

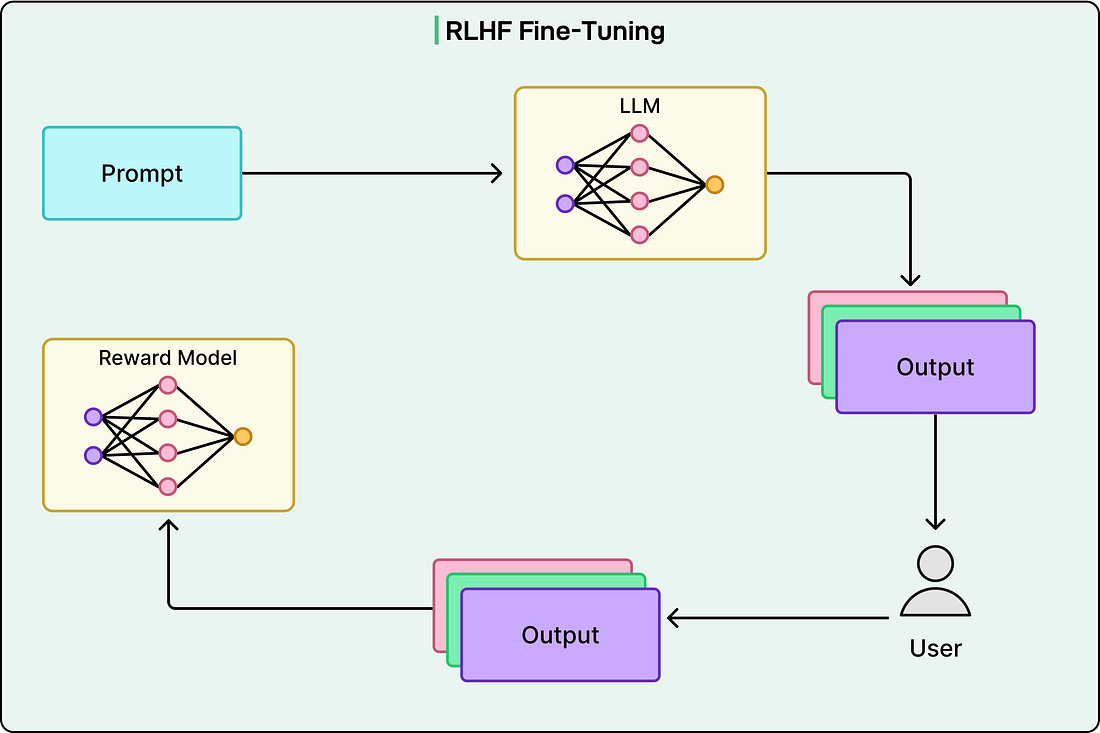

Fine-Tuning and RLHFAfter pretraining, an LLM is excellent at predicting what comes next in text sequences, but this doesn’t make it a helpful conversational assistant. If given a prompt that starts with a question, the pretrained model might continue with more questions rather than providing an answer. It simply completes text in statistically likely ways based on the patterns it has learnt. Transforming this autocomplete system into the helpful assistants we interact with requires additional training phases. Supervised fine-tuning addresses this gap by training the model on carefully curated examples of good behavior. Instead of learning from general text, the model now trains on prompt-response pairs that demonstrate how to follow instructions, answer questions directly, and maintain a helpful persona. These examples might include questions paired with clear answers, instructions paired with appropriate completions, and conversations demonstrating polite and informative dialogue. This dataset is much smaller than pretraining data, perhaps tens of thousands to hundreds of thousands of examples rather than billions, but each example is precisely constructed to teach desired behaviors to the LLM. The training process remains the same: predict the next token, calculate loss, adjust parameters. However, now the model learns to predict tokens in these ideal responses rather than arbitrary internet text. Supervised fine-tuning provides significant improvement, but it has limitations. Writing explicit examples for every possible scenario the model might encounter is impractical. This is where reinforcement learning from human feedback (RLHF) provides further refinement. The process begins with the model generating multiple responses to various prompts. Human raters then rank these responses based on quality, helpfulness, and safety. These rankings train a separate reward model that learns to predict scores human raters would assign to any response. See the diagram below: Once the reward model exists, it guides further training of the language model. The language model generates responses, the reward model scores them, and the language model updates to produce higher-scoring responses. There’s a careful balance here: the model should improve according to human preferences while not deviating so far from its pretrained version that it loses core knowledge and capabilities. This entire process can iterate multiple times, with improved models generating new responses for human evaluation. Deploying the ModelOnce training completes, the model undergoes a comprehensive evaluation before deployment. Developers test it on various benchmarks that measure different capabilities such as language understanding, reasoning, mathematical ability, coding skills, and factual knowledge. Safety testing runs in parallel, examining the model’s tendency to generate harmful content, its susceptibility to adversarial prompts, and potential biases in its outputs. The model also undergoes optimization for deployment. Training prioritizes learning capability over efficiency, but deployed models must respond quickly to user requests while managing computational costs. Techniques like quantization reduce the precision of parameters, using fewer bits to represent each number. This decreases memory requirements and speeds up computation while typically preserving most of the model’s capability. Other optimizations might involve distilling knowledge into smaller, faster models or implementing efficient serving infrastructure. Deployment isn’t an endpoint but rather the beginning of a continuous cycle. Organizations monitor how users interact with deployed models, collect feedback on response quality, and identify edge cases where the model fails or behaves unexpectedly. This information feeds directly into the next training iteration. When someone uses an LLM today, they’re interacting with the culmination of this entire process, from data collection through optimization. ConclusionThe journey from raw internet data to conversational AI represents a remarkable achievement at the intersection of data engineering, mathematical optimization, massive-scale computation, and careful alignment with human values. What begins as terabytes of text transforms through preprocessing, tokenization, and billions of parameter adjustments into systems capable of generating coherent text, answering questions, writing code, and engaging in sophisticated dialogue. Understanding this training process reveals both the impressive capabilities and fundamental limitations of LLMs. For software engineers working with these systems, understanding the training process provides crucial context for making informed decisions about when and how to deploy them. SPONSOR USGet your product in front of more than 1,000,000 tech professionals. Our newsletter puts your products and services directly in front of an audience that matters - hundreds of thousands of engineering leaders and senior engineers - who have influence over significant tech decisions and big purchases. Space Fills Up Fast - Reserve Today Ad spots typically sell out about 4 weeks in advance. To ensure your ad reaches this influential audience, reserve your space now by emailing sponsorship@bytebytego.com. |

How LLMs Learn from the Internet: The Training Process

WE BRING YOU THE BEST!

01 December

Users_Online! 🟢

Comments

Search This Blog

Random Posts

Most Popular

Save thousands on your next car!

27 November

Companies are looking for Sales Representative

27 November

Phew! This is your problem now.

29 November

💬 Makathandeka Thah commented on a post

27 November

Featured post

Ad Space

Created By SoraTemplates | Distributed By Blogger Templates

0 Comments

VHAVENDA IT SOLUTIONS AND SERVICES WOULD LIKE TO HEAR FROM YOU🫵🏼🫵🏼🫵🏼🫵🏼